“Machine politics” is a phenomenon sometimes seen in an urban political context, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Political machines are characterized by tight organization and a strong centralized leadership, typically in the form of a “boss.”

They operate by dominating the political landscape. The “machine” gets its name from its ability to reliably, even mechanically, turn out the votes needed to get its members elected and its measures passed.

Origin of “Machine Politics”

One of the most famous examples of political machines was Tammany Hall, which operated in New York City from 1789 until some time in the 1950s.

Tammany Hall opened its doors as a benevolent institution, and in theory the group was concerned with helping out immigrants and the needy; in fact, it acted as a vote-collecting arm of the local Democratic party, playing on ethnic divisions in the city to help get out the vote for the right candidates.

Like other political machines, Tammany Hall was rife with corruption. It is known for leaders like William Plunkitt, who famously held forth about the difference between honest and dishonest graft (Plunkitt was all for honest graft).

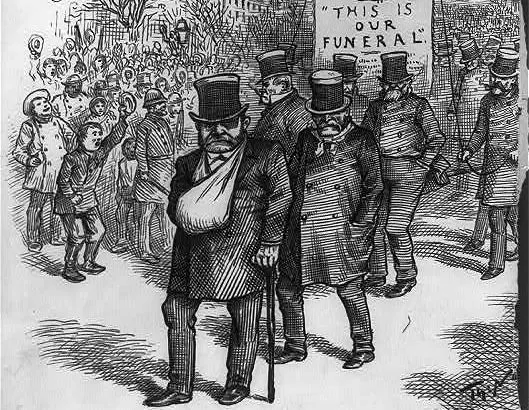

Tammany Hall’s best-known leader was probably William Magear Tweed, usually referred to as Boss Tweed.

Tweed, born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, began his political career as an alderman and quickly worked his way up.

He served a term in Congress but was more interested in local, New York politics.

By 1860, he had established control over the nomination process for every significant elected office in the city, and commanded the loyalty of Democratic leaders.

Tweed used his connections to exact payments from businesses and ordinary citizens; he had countless schemes involving faked leases, padded bills, and trumped-up fees.

Tweed’s corruption was both notorious, and fairly standard; machine politics and corruption often go hand in hand.

At the same time, Tammany Hall did act as a safety net for many New Yorkers, providing social services that the government wasn’t equipped for.

Tammany Hall’s leaders sent baskets of food to the poor; they also helped out any of their supporters who ran into legal troubles.

Tammany Hall also helped get white men who did not own property the right to vote. The result was a loyal base of voters who could be relied on to support any of Tammany Hall’s favored politicians.

In a book titled Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics, the historian Terry Golway takes a more positive view of Tammany Hall than is usually seen.

Golway argued that Tammany Hall’s critics were often motivated by anti-Irish sentiment.

He also argued that Tammany Hall did a lot of good, smoothing the way for the city’s poor and especially for newly arrived immigrants.

As Golway told National Public Radio:

Every history of Tammany Hall is told as a true-crime novel, and what I’m trying to suggest is that there’s this other side. I’m arguing, yes, the benefits that Tammany Hall brought to New York and to the United States do outweigh the corruption with which it is associated. I’m simply trying to complicate that story…

Tammany Hall was there for the poor immigrant who was otherwise friendless in New York.

Examples of “Machine Politics” in a sentence

- The machine politics of the 19th century were characterized by a political system controlled by a small group of party bosses who wielded significant power and influence.

- The rise of machine politics led to widespread corruption and manipulation of the electoral process.

- Despite efforts to reform the system, machine politics continues to be a pervasive force in many cities and states across the country.