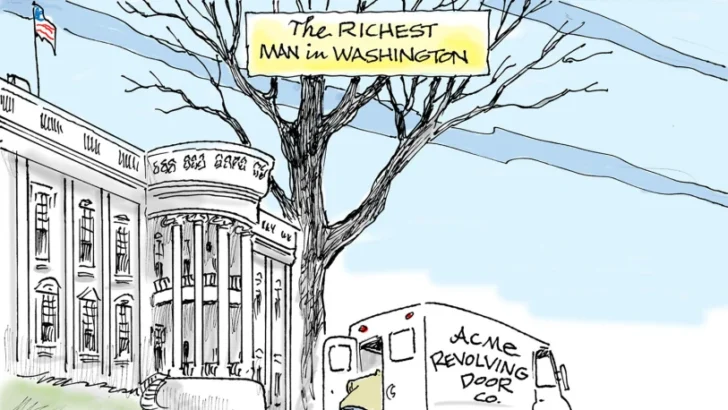

The term “revolving door” refers to the practice where individuals move between roles in the public and private sectors, especially within industries that they had been responsible for regulating or influencing.

This phenomenon is often viewed with skepticism, as it can create conflicts of interest or the appearance thereof, and perpetuate a system where influence and access are traded as commodities.

Critics argue that the practice compromises the integrity of both governmental agencies and private enterprises.

More on “Revolving Door”

The classic euphemism for ex-government officials who “swing” between public service and considerably higher-paying jobs downtown in the D.C. lobbying and influence community.

Washington is filled with former officials who trade on their former positions in the private sector, only to later return to a government salary. Dick Cheney was hired to head the oil-services giant Halliburton in 1995 in large part owing to his government connections.

Cheney had served as chief of staff to Vice President Gerald Ford, was a Republican congressman from Wyoming for a decade, and defense secretary in the George H. W. Bush administration. Cheney, of course, reentered government six years later when he became vice president alongside President George W. Bush.

The watchdog group Center for Responsive Politics in 2013 identified more than 400 formers who now work in lobbying.

Indiana Republican Dan Coats has probably had more turns through the revolving door than anyone now in office. He was a congressman for eight years before being appointed to an open Senate seat. He served for ten years and retired after the 1998 elections.

Coats practiced law for a couple of years, then took another turn through the revolving door back into government. Ex-Senator Coats served as ambassador to Germany from 2001 to 2005, during Bush’s first term.When that government gig was done, it was back to the more lucrative private sector for Coats.

In 2007 Coats served as co-chairman of a team of lobbyists for Cooper Industries, a Texas corporation that moved its principal place of business to Bermuda, where it would not be liable for U.S. taxes. In that role, he worked to block Senate legislation that would have closed a tax loophole, worth hundreds of millions of dollars to Cooper Industries.

The New York Times also reported that Coats was co-chairman of the Washington government-relations office of King & Spalding, with a salary of $603,609—more than triple what senators were earning at the time.

Coats moved back to Indiana and ran for the Senate in 2010, coaxing Democratic senator Evan Bayh into retirement rather than face a tough race in what was already shaping up as a strong Republican year. Coats won easily. Sticking to the meta-phor, Coats told the Indianapolis Star: “Throughout my life, whenever a new door has opened, I chose to accept the challenge, instead of playing it safe.”

The Center for Responsive Politics, in a 2011 report, high-lighted another emerging trend: “reverse revolvers” who went from lobbying to working on Capitol Hill.

It found that the number of ex-lobbyists in Congress had more than doubled within a few years, with several major companies’ former lobbyists working for the committees that they once lobbied.

Topping the list with thirteen ex-employees was AT&T/SBC Communications Inc., followed by defense giant Lockheed Martin and the pharmaceutical titan Roche Group.

From Dog Whistles, Walk-Backs, and Washington Handshakes © 2014 Chuck McCutcheon and David Mark.

Use of “Revolving Door” in a sentence

- The revolving door between Capitol Hill and K Street has long been a subject of ethical debate, raising questions about undue influence over legislation.

- After serving as the FDA Commissioner, she joined a pharmaceutical company, exemplifying the revolving door that skeptics say undermines regulatory rigor.

- Critics contend that the revolving door phenomenon is corrosive to democracy, as it allows former politicians to leverage their government connections for private gain.