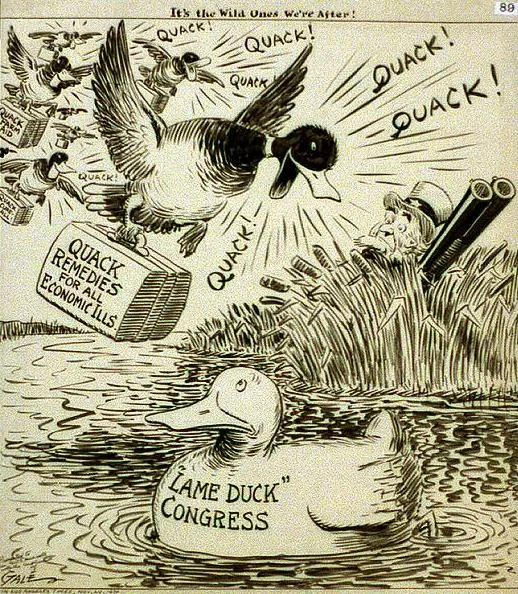

A “lame duck session” is when the House or Senate reconvenes in an even-numbered year following the November general elections to consider various items of business.

It’s called this because some of the lawmakers who return for this session will not be in Congress when it reconvenes in January.

Hence, these sessions are informally called “lame duck” members participating in a “lame duck session.”

It’s their last chance to make their mark on the nation’s laws.

As a result, lame duck lawmakers are sometimes very unpredictable.

They don’t need to raise money for reelection, so they are relatively more willing to take unpopular positions and stand up to lobbyists and other special interests.

Of course, they’re probably also less accountable to their constituents than lawmakers who intend to run again for their seats.

History of the “Lame Duck Session”

The first lame duck sessions in the modern Congress began in 1935, when the 20th Amendment to the Constitution took effect.

Under this amendment, which was ratified in 1933, Congress is scheduled to meet in a regular session on January 3 of each year.

Formally, a session of Congress ends when Congress adjourns sine die.

Use of “Lame Duck Session” in a sentence

- During the lame duck session of Congress, outgoing legislators who lost re-election or chose not to run often find themselves unburdened by electoral considerations, enabling them to take politically risky votes.

- Historically, significant legislative action has sometimes occurred during lame duck sessions, such as the ratification of treaties or the passage of controversial bills.

- However, the efficacy of a lame duck session often depends on the political climate, with heightened partisanship potentially leading to gridlock even when the electoral stakes are ostensibly lowered.